Burnt toast and dinosaur bones have a common trait, according to a new, Yale-led study. They both contain chemicals that, under the right conditions, transform original proteins into something new. It’s a process that may help researchers understand how soft-tissue cells inside dinosaur bones can survive for hundreds of millions of years.

A research team from Yale, the American Museum of Natural History, the University of Brussels, and the University of Bonn announced the discovery Nov. 9 in the journal Nature Communications.

Fossil soft tissue in dinosaur bones has been a controversial topic among researchers for quite some time. Hard tissues, such as bones, eggs, teeth, and enamel scales, are able to survive fossilization extremely well. Soft tissues, such as blood vessels, cells, and nerves — which are stored inside the hard tissue — are more delicate and thought to decay rapidly after death. These soft tissues are composed mainly of proteins, which are believed to completely degrade within about four million years.

Yet dinosaur bones are much older, roughly 100 million years old, and they occasionally preserve organic structures similar to cells and blood vessels. Various attempts to resolve this paradox have failed to provide a conclusive answer.

“We took on the challenge of understanding protein fossilization,” said Yale paleontologist Jasmina Wiemann, the study’s lead author. “We tested 35 samples of fossil bones, eggshells, and teeth to learn whether they preserve proteinaceous soft tissues, find out their chemical composition, and determine under what conditions they were able to survive for millions of years.”

The researchers discovered that soft tissues are preserved in samples from oxidative environments such as sandstones and shallow, marine limestones. The soft tissues were transformed into Advanced Glycoxidation and Lipoxidation end products (AGEs and ALEs), which are resistant to decay and degradation. They’re also structurally comparable to chemical compounds that stain the dark crust on toast.

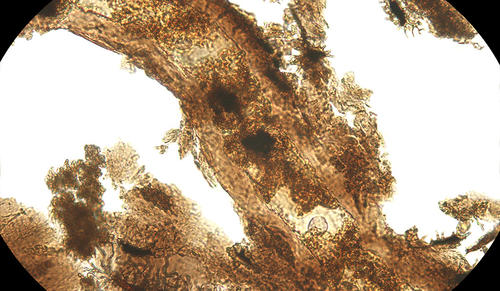

AGEs and ALEs are characterized by a brownish color that stains fossil bones and teeth that contain them. The compounds are hydrophobic, which means they are resistant to the normal effects of water, and have properties that make it difficult for bacteria to consume them.

Wiemann and her colleagues made their discovery by decalcifying fossils and imaging the released soft tissue structures. They applied Raman microspectroscopy — a non-destructive method for analyzing both the inorganic and organic contents of a sample — to the extracted fossil soft tissues. During this process, laser energy directed at the tissue causes molecular vibrations that carry spectral fingerprints for the chemicals that are present.

Experimental maturation initiates glycoxidation/lipoxidation in a fresh eggshell matrix sample. The local browning of the otherwise translucent sample represents the formation N-heterocyclic polymers. (Image credit: Jasmina Wiemann/Yale University)

Experimental maturation initiates glycoxidation/lipoxidation in a fresh eggshell matrix sample. The local browning of the otherwise translucent sample represents the formation N-heterocyclic polymers. (Image credit: Jasmina Wiemann/Yale University)

Co-author Derek Briggs, Yale’s G. Evelyn Hutchinson Professor of Geology and Geophysics and a curator at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, said the study points to localities where soft tissue may be found in fossil bones, including sandstones deposited from rivers, dune sands, and shallow marine limestones.

“Our results show how chemical alteration explains the fossilization of these soft tissues and identifies the types of environment where this process occurs,” Briggs said. “The payoff is a way of targeting settings in the field where this preservation is likely to occur, expanding an important source of evidence of the biology and ecology of ancient vertebrates.”

Additional co-authors of the study are Matteo Fabbri from Yale, Martin Sander and Tzu-Ruei Yang from the University of Bonn, Koen Stein from the University of Brussels, and Mark Norell from the American Museum of Natural History.